10 Things You Can Learn from Mikhail Botvinnik

Mikhail Botvinnik is one of the classics every player should study.

He was the 6th World Champion and held the title for almost 15 years, though not consecutive.

But he is also widely known as the Patriarch of the Soviet Chess School, as he trained many strong Grandmasters, with some of the most famous students being Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov and Vladimir Kramnik.

He was born in the Soviet Union, in a region of what is now Saint Petersburg. He learned chess at the age of twelve, from a school friend of his older brother’s and fell in love with the game immediately. The first success came one year later, in 1924, when he won his school’s championship. In 1925 he beat the World Champion Jose Raul Capablanca in a simultaneous exhibition that was held during the Moscow tournament.

In 1931, at the age of 20, Botvinnik became the Soviet Champion and repeated this achievement for five more times during his chess career. His contention to the World title started in 1938, when he received support from the Soviet officials to challenge Alekhine. However, the match had to be postponed because of the start of the World War II. A second try to arrange the match in 1946 was also put to an end by Alekhine’s death. Consequently, a tournament between five players was arranged in 1948 in order to determine the new World Champion. He won it convincingly, with 14 out of 20 points, three points ahead of the second-placed Vasily Smyslov.

Although he kept his World Championship title for most of 1948 to 1963 (except 1957-1958 and 1960-1961), chess was not his only career. He was an electrical engineer and computer scientist and applied his knowledge in chess, being a pioneer in computer chess.

There are a lot of things an aspiring chess player can learn from this legend. The first thing I want to highlight, before we get to the chess part, is his training style. Later on, he applied the same ideas in his own chess school. He was known to have a rather narrow opening repertoire and focused on understanding the resulting positions better than his rivals rather than rely on tactical tricks that could only be used once.

This is especially important nowadays, when there is a lot of information online and many beginners fall for the trap of learning tricks that could bring them a quick victory. The problem with this is that, in general, they are bad openings where, if the opponent doesn’t fall for the trick, they will be left with a much worse position.

Secondly, he is the one who showed the importance of annotating one’s games and studying other strong players’ ones. Today this is a well-known practice and we know that the best way to learn and improve our play is by analyzing our own games. Both wins and losses are important to review. A win is rarely perfect and there might still be mistakes that the opponent didn’t take advantage of. In the case of losses, it is only natural to try to understand where we went wrong and why we made that certain mistake.

He had the vision of the modern chess player, who needs to be prepared on every aspect. Besides the chess training, he was also an adept of physical training – something that many top players apply nowadays.

One very interesting aspect of the way he was training is that he was trying to recreate the atmosphere of the tournament in his own sessions. For example, after performing below the expectations in the 1940 USSR Championship because, as he said, he couldn’t concentrate in a party-like atmosphere, filled with noise and tobacco, he decided to train in such an atmosphere for his next tournament. His second, Ragozin, arranged for him to play training matches in rooms filled with smoke and noise; he even slept in the playing hall without opening the windows.

Moving on to his games and playing style, he is a great player to learn strategy from. He was great in complex positions and he has played more than one positional masterpiece. If you want to improve your positional play and polish your ability of finding the right plan in complicated positions, Botvinnik is the player to look at.

Another characteristic of his play is that he liked tense positions with chances for both sides. He enjoyed playing for the initiative and didn’t back down from sacrificing material for compensation. He often used the positional sacrifices; the purpose was not an immediate win, but creating a complicated position, where he had chances of putting pressure on the opponent.

A famous idea can be seen in his game against Liublinsky:

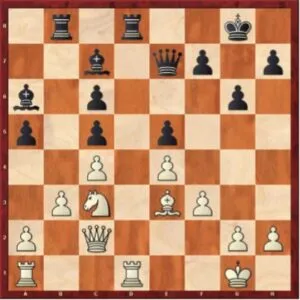

Liublinsky, V – Botvinnik, M, Moscow, 1943

Black to play

Black’s pawn structure has been damaged, so on long term, white should be able to attack the weaknesses and eventually win them. If black stays passive, it will be a slow and painful game. So, Botvinnik decides to complicate the game with the move 25…Rd4!? After white takes the rook, black will be an exchange down, but will have the bishop pair, a powerful center and more space. White’s rooks have no open files, so it will be difficult for white to use his material advantage.

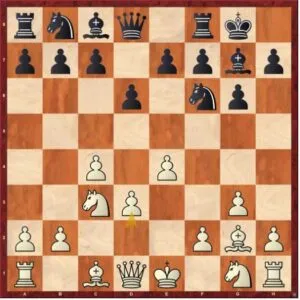

In the opening, his ideas for black in the Semi Slav are still being used today. The Botvinnik system, where black plays 5…dxc4, giving up the center, but gaining (and defending) a pawn, is considered one of the most complicated lines to learn.

The Botvinnik System in the Semi Slav

Today the theory has been developed widely and many players employ his ideas as a weapon for black. At that time, his idea was revolutionary and we can say that it has set the ground for modern chess. Black gets a pawn majority on the queenside and the game become sharp quickly. The following game against Arnold Denker is a great example of how wild the game can get:

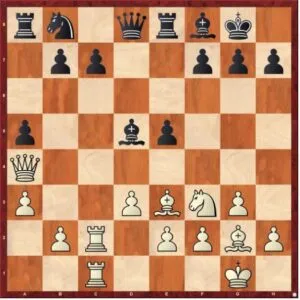

In the English Opening, the Botvinnik system is considered a solid option for white. His idea was to play with a pawn on e4 and develop the kingside knight to e2:

The Botvinnik System in the English

This position usually arises after the moves 1.c4 Nf6 2.g3 g6 3.Nc3 Bg7 4.Bg2 0-0 5.e4 d6 6.d3. After the knight is developed to e2, white has a solid, but flexible set-up, with attacking chances on both wings.

Botvinnik was a complete player and his games should be studied in order to improve all aspects of the game. He had groundbreaking ideas in the opening, played very well strategically and was very good in the endgame. He was comfortable in complicated positions, where he had the initiative and was able to put pressure on the opponent. He also has many beautiful tactical finishes, where he found brilliant ideas. The following game is very well known:

Botvinnik, M – Portisch, L, Monaco 1968

Black has just played 15…Nb8, probably preparing …bc6 and Nd7-f6, relying on the fact that 16.Rxc7 could be met with the same 16…Bc6, trapping the rook.

However, this is exactly what Botvinnik played! Calculating better than his opponent, he found a beautiful idea that immediately wins him the game. Can you calculate the line until the end?

https://thechessworld.com/store/product/learn-from-mikhail-botvinnik-with-im-boroljub-zlatanovic/

Comments: