Equal Chess Positions: Playing Them

Equal Chess Positions: The engines really don’t care about us, humans, who have to play a position that they happily evaluate as equal. Feed it a symmetrical position with equal material and no apparent weaknesses and it will tell you it is “just equal,” sometimes even a “dead draw.”

One type of symmetrical position arises from the Queen’s Gambit Accepted when White takes on c5 and then the queens are exchanged. After 1 d4 d5 2 c4 dc 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 e3 e6 5 Bc4 c5 6 0-0 a6 7 dc Qd1 (or 7…Bc5 8 Qd8 Kd8) the endgame is equal, undoubtedly, but here it is fitting to paraphrase George Orwell and one of his most famous quotes: all positions are equal, but some positions are more equal than others.

Many strong players have lost these endgames with both colors. Perhaps most famously Vladimir Kramnik with White tortured Garry Kasparov in Game 4 of their match in 2000 and Boris Spassky did the same to Bobby Fischer in their match in 1992. I still find it surprising and difficult to understand why Fischer chose the Queen’s Gambit Accepted as a defensive weapon in that match. In both of these matches, the Black players suffered greatly in this seemingly harmless (and definitely equal!) endgame.

But Boris Spassky played the Queen’s Gambit Accepted with Black as well. In fact, he was very successful with it, having won more than a few games against strong players in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

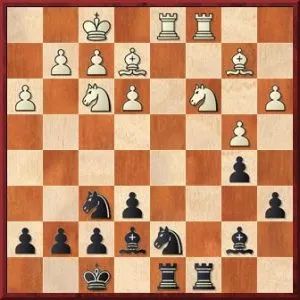

The position below is taken from Spassky’s game against Pomar Salamanca. And, it was played in 1971, a period when Spassky was a World Champion.

Equal Chess Positions: Here is what I can say about this position…

The position is almost identically symmetrical. The main difference is the position of the queen’s knights. White’s one is on c3 and Black’s one is on d7. This slight difference favors Black, as the knight on d7 is more flexible – it can go to b6 and from there target the vulnerable squares c4 and a4. The knight on d7 also does not block the long diagonal for the bishop on b7, whereas the knight on c3 does render the bishop on b2 inactive.

Still, these slight differences in a position with no weaknesses for either side should not account for much, at least not if you ask the engine.

It happily chirrups around the triple zero marks and indicates as best the move played by Pomar:

17 Nb1

The idea is obvious, to improve the position of the knight and the bishop at the same time. But if White’s best is to spend two moves to achieve what Black already has, then, strangely enough, we will have Black being White as he will have the extra move to make! To illustrate my point, if now Black plays 17…h6 then after 18 Nbd2 we will have a completely symmetrical position with Black to move!

This means that White’s previous play had been imprecise as he managed to waste time and give away the advantage of the first move to Black. For an engine, this does not mean a thing, but for a human, the realization that he had played sub-optimally beforehand can have a serious psychological impact. Spassky was probably amused by all this, which did not prevent him to find a more useful move than …h6.

17…Nd5

Black starts to become active in the exact moment White removed a piece that controlled the center.

18 Nbd2 N7b6

White achieved his desired set-up but Black improved the position of both of his knights. They are targeting c3, c4, and a4. This is still very much equal to the engine. But, to a human Black has the initiative. And, this makes White’s position more unpleasant to play. Curiously enough, Pomar continues to play the engine’s preferred moves.

19 Nb3

Also targeting the vulnerable squares on c5 and a5, something Black did on his previous move.

19…Na4

Not only winning a tempo by attacking the bishop but also covering c5 and intending to penetrate on c3. Once a knight lands there White will have to take it and Black will obtain the bishop pair.

20 Bd4 Ndc3 21 Bc3 Rd1 22 Bd1 Nc3

Black won the bishop pair and exchanged a pair of rooks along the way. To a human this would already mean a significant advantage, but not to an engine. Pomar’s move is still the preferred choice, with the following sequence:

23 Be2 Ne2 23 Rc8 Bc8 24 Ke2 f6

Leading to a typical endgame of a pair of bishops against a pair of knights. This is a big advantage for a human and almost 0.00 position for an engine. As you can imagine, Spassky won the ensuing endgame. A few moves later Pomar stopped playing like an engine and blundered into a lost position.

This probably means that a human would likely lose this position with White whereas an engine would not. Perhaps that is why humans do not like playing against engines anymore.

Still, what I find intriguing about the above example (and other, similar ones) is how the position imperceptibly changed from one where all seemed well and good for White, a symmetrical position without weaknesses and mass exchanges likely to happen along with the c and d-files, to a one where White was fighting for a draw. To make it even more confusing, White played all the engine’s preferred moves!

Equal Chess Positions: How did this happen?

The answer to this question lies in the George Orwell paraphrased quote above. The starting position from where we started our analysis was objectively equal, but it was not a type of equality where all resources for further struggle are exhausted.

Furthermore, the “small” differences in the position favored Black and this shaped the tendency in the position in Black’s favor. As this tendency developed, with both sides making the best moves, it led to a position with a clear advantage to Black, which, and this is perhaps the most surprising thing, may still be drawn! The moment where we stop our analysis is most likely still objectively a draw, but as engines have taught us, objectivity has nothing to do with the actual playing out of the position.

Humans are fallible and to them, objectivity in such positions matters little. The White player was suffering and he succumbed to the pressure.

The Game

Equal Chess Positions: The Moral

I think the moral of this story is obvious. Just remember George Orwell and try to look at the positions with human eyes.

Not all zeroes are created equal.

Comments: