Fortresses – What do you need to know?

“I don’t believe in fortresses.” – Magnus Carlsen

I understand Carlsen’s famous quote, not at face value, but rather as an understanding of chess’s nearly infinite possibilities. Carlsen himself has shown in a lot of his games and how seemingly easily drawn games can be won by finding hidden resources in the position.

Still, fortresses do exist in chess. Even Carlsen himself has stumbled upon one or two in his career. Perhaps the costliest one was in the fourth game of the match with Karjakin, when in a relatively easily won position he allowed Karjakin to build one. Later in the match, the missed chances of an early lead could have cost Carlsen dearly.

In this article, I would like to take a look at one specific fortress that is quite typical of the symmetrical structure it can arise from. These symmetrical structures are very common and can happen from many openings – the Queen’s Gambit Accepted, the Queen’s Gambit Declined, the Catalan, the Nimzo-Indian and probably some others too, either directly or by transposition to the above openings.

Symmetrical structures can be very deceptive. It may appear at first sight that they would lead to a draw quickly, but in fact, having the initiative in such positions is of utmost importance because that initiative is difficult to contain exactly because of the symmetry in the position. In symmetrical positions, a counter play is very hard to find.

Having the advantage of the bishop pair in symmetrical positions is a big advantage. The bishops can easily play on both wings and the unopposed bishop can wreak havoc attacking the opponent’s pawn structure.

The fortress I will now show is of great practical value. It can help the defending side orientate himself in these positions when the opponent has the bishop pair. It is always easier to play when you know what you should be striving for.

Coincidentally, I first saw this the fortress in a game by Magnus Carlsen.

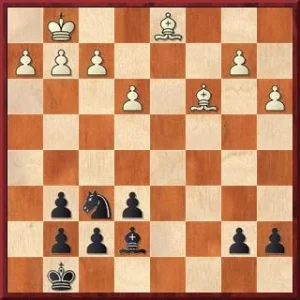

This is the position from the game Carlsen-Anand from the Dortmund tournament in 2007. It appears that Black is in for a very long defense here, having no obvious compensation for White’s bishop pair.

But in fact, Anand willingly went in for the simplifications that led to this position. He already foresaw the fortress that helps him easily make a draw, practically on autopilot.

22…Ne4!

The knight is on the way to d6. The knight is the key piece that holds the fortress together and d6 is the square from where it will control everything.

23 Be1g5!

The pawns need to be arranged on the dark squares. This may seem unnatural at first, especially with Black having a dark-squared bishop, but the idea will be revealed in no time.

24 Kf1 b6

Continuing with the plan to put the pawns on dark squares.

25 Ke2 Bf6

Since the pawns will be on dark squares Anand gets the bishop outside of the pawn chain first.

26 Bc2 Nd6

There was no need to do it earlier, as the centralized knight was quite good on e4, but now once attacked the knight finally arrives at its destination.

27 b3 Kf8 28 Bd3 Ke7

Black centralized the king since there was no rush in setting up the fortress quickly. White was not threatening anything, slowly improving his position, so Black did the same and took the time to improve the position of his king.

29 g4 Bb2 30 a4 f6! 31 b4 e5!

And here it is! The fortress has been constructed. You can now see how harmoniously the pawns and the knight control every possible access to Black’s position. The knight controls the light squares and the pawns control the dark squares – that is why it was important to put them on dark squares! Black’s bishop is outside the pawn chain and can just shuffle around – Black’s position is impregnable.

It is important to note that the move f4 will not change anything. After a double exchange, there another Black pawn will arrive on g5, taking control of the f4-square. But even without control over f4 Black has a fortress: the squares g5, f5, e5, e4, d4, c4, and c5 are all under control, making it impossible for the White king to penetrate Black’s position. And without the king going forward White cannot improve his position.

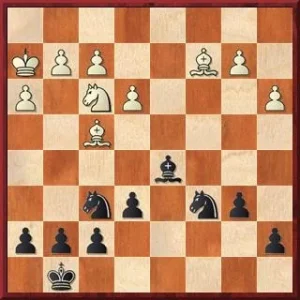

I already knew the fortress from the Carlsen-Anand game when I played my game against GM Tregubov in 2010. The following position could have arisen in the game and with my previous knowledge, I easily saw the line that led to safety.

White has the pair of bishops and hopes for a long grind. But I knew that I had to strive for a position with a knight on d6 and pawns on dark squares. Then it was easy to find the solution:

22…Bf3! 23 gf e5!

The first and most important pawn arrives on a dark square.

24 Bg5 h6 25 Bf6

Otherwise, the bishop will be dead on g3 after 25 Bh4 g5.

25…gf 26 Kg3 Na5!

With the idea of …Nc4, attacking White’s pawns. Gaining tempo with this threat the knight rushes to the ideal spot on d6.

27 a4 Nb7 28 f4 Nd6

The fortress has been set-up and the position is a dead draw now.

Unfortunately, my opponent did not go for this line allowing me to draw in such an elegant way and the game continued in another direction.

Knowledge of fortresses is very practical. Even though they are most often used in theoretical endgames, where the defending side manages to draw against overwhelming material advantage, some fortresses can be used in playable endgames, like the ones we saw above.

So the moral of this story about fortresses perhaps lies in the proof that the words of Magnus Carlsen should not be taken seriously!

Or, rather, as I explained in the beginning, they should be understood at another level – that even though fortresses do exist in chess, the game provides ample resources for breaking them down, as Carlsen has demonstrated on more than one occasion.

Good luck!

Comments: