Middle Game

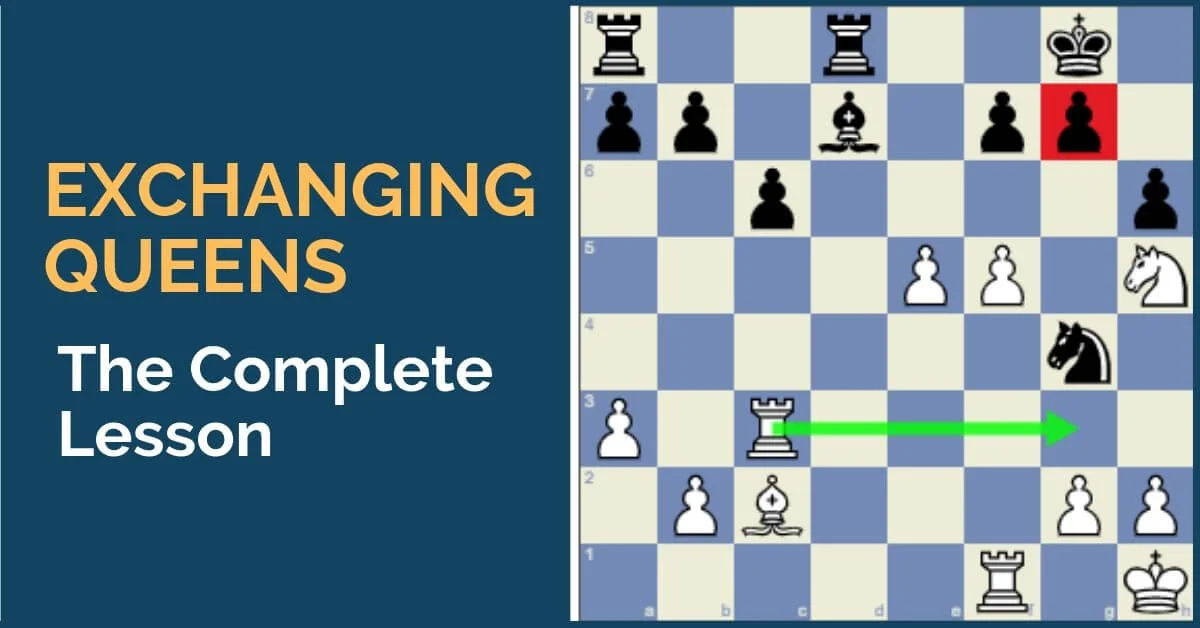

In every game we play, trading pieces is inevitable. However, this shouldn’t be done automatically and it is important to choose the right moment and the right pieces to trade. Today we are going to talk about queens and when you should decide to trade them off and when to keep them on the board. […]

The Carlsbad pawn structure refers to the formation that arises usually, but not exclusively, from the Exchange Variation of the Queen’s Gambit. It can also be reached from other Queen’s Pawn openings such as the Nimzo-Indian and Grunfeld. We find the same structure, but this time with reversed colors, in the Exchange Variation of the […]

Positions with the isolated pawn are often misunderstood, which many times leads to the fear of playing this type of position. The common concept is that the isolated pawn is a weakness (and it is!) and we know that we should avoid creating weaknesses in our position. This general idea is correct, but there are […]

A very important feature of the position and one that we should pay special attention to during every game we play is the pawn structure and the changes that it might suffer throughout the game, as your plans should also change with it. The study of the most important pawn formations will not only help […]

Ever since we start learning chess we are taught to look for active moves; moves that control the center and help improve our position. We are also told to search for ways to put our opponent in an uncomfortable situation, seek the initiative and try to build an attack whenever this is possible. All the […]

The pawn majority is an important concept in chess and it refers to the side of the board where you have more pawns than your opponent. The main plan in this type of structure is to find the right moment to advance the pawns, gain more space and cramp your opponent’s position. However, as it […]

A good player is always lucky. This famous quote attributed to the third World Champion Jose Raul Capablanca means that one way or another, the stronger player will always find a way to escape and get a good result. We see it all the time in tournament practice or even casual play against experienced players. […]

“I don’t believe in fortresses.” – Magnus Carlsen I understand Carlsen’s famous quote, not at face value, but rather as an understanding of chess’s nearly infinite possibilities. Carlsen himself has shown in a lot of his games and how seemingly easily drawn games can be won by finding hidden resources in the position. Still, fortresses […]

The hanging pawns structure is a very common one in the chess game. By definition, we call hanging pawns when there are two pawns joined together but isolated from the rest of the pawn chain. They are usually on the fourth rank; if found already beyond they are no longer hanging, but two very dangerous […]

Typical maneuvers that every chess player must know. The Isolated Central Pawn or IQP (isolated queen’s pawn) is one of the classic structures in that every player must learn how to play with both sides. It is a unique structure with established characteristics and plans of playing with it or against it. Part of chess […]